Skaters of London

Fluid Constructions

Chilled by the dry winter air flowing over a swollen River Thames, the hard concrete pile of the Southbank Centre reveals itself — solid, immovable, threatening — supported by the mushroom columns that have become symbols of strength and hope for the subculture that has thrived for decades at the Undercroft.

The Southbank Centre is an establishment giant in the heart of the Queen’s Walk. Their coexistence is a contradiction, opposites yet kindred. Above, mainstream folk dwell, where in warmer seasons crowds gather to experience the pleasantries on offer. Art from across the planet, prepackaged as a consumable commodity; its historic significance explained to its visitors from city and wider, details that are so easily forgotten.

As an open space beneath the riverside façade of the Queen Elizabeth Hall, the Undercroft is adorned with ever changing and evolving graffiti, logos and personalised tags. Otherwise starkly bare in ornamentation, its brutalist construct entombs frequent sounds of scratching wheel against polished concrete that jar, and are heard alongside whoops and cheers that tranquillise as doubtless a trick lands. The sounds, evoked and heard over decades, a constant undulation through the wall of sound that rides close to cacophony. Listen carefully and one’s ear picks out a rhythm that scores between the harsh and the smooth.

The Undercroft is culture in situ; one actively forming in front of our very eyes. Perhaps the millions of steps stepping past may never reflect upon the site’s true importance, one that perhaps never really reveals its totality. Dismissing the Undercroft is to dismiss the chance to experience history today. A landscape perfect for skateboarding. The very design of the Southbank Centre uniquely enabled this group’s existence, its location and cultural significance a refuge for so many.

——————

Early in the day, not yet peak skating time, the space is stilled by silence. I stumble upon a trio from across the site, dressed in skating apparel. I recognise one of the trio as Stuart McClure and tentatively approach. Obscured by a beanie hat and dressed in an oversized winter coat, Matt Nelmes is at first hard to recognise. He offers his hand to nonchalantly introduce the third sitting on a ledge. “This is Henry, one of the architects of Long Live Southbank.”

Matt and Stuart soon depart, I sit beside Henry, our backs to the Thames, sloshing waves hit the banks behind; skateboard tucked under his knees. Our eyes focused on the empty Undercroft ahead. We discuss the impressive achievement of overturning Southbank’s planning permission in 2013 and he offers me his take on why they won against such a colossal cultural institution.

“Everything is in flux. They were rigid and we weren’t. We were able to bend ourselves to fit what we had to do and we pushed them back. Nothing is solid in this world, the concrete we sit on may look so to our eyes but if you go deep enough you’ll find it’s all fluid and in motion.

“You couldn’t have pitched it more perfectly. Look at this place, the way we are situated, speaks about class and all sorts.”

He seems scruffy at first glance, wearing a beanie, the smoke of his rolled up cigarette catches in his short, light blonde beard. He describes with confidence the reason they won, a victory they had to fight for, not a privilege owed. Henry Edwards-Wood’s laid back nature hides a simmering intensity.

Southbank, The Southbank Centre & The Undercroft

A stone's throw from the heart of British political power and justice, the London borough of Lambeth’s South Bank region has historically been a site of entertainment. Dating back to medieval times, with such lures as music halls, bear-bating and prostitution, today’s Southbank Centre began its life in 1948, staging The Festival of Britain.

Expansion in the 1950s saw the establishment grow to the largest arts centre in Europe, opening the Hayward Gallery, Purcell Room and Queen Elizabeth Hall. A popular site with tourists and Londoners, the stretch between the bridges Lambeth and Tower sees a relentless fall of feet though the Queen’s Walk. A fifteen mile promenade along the southern bank of the River Thames, the pedestrian walkway was created as part of the 1977 Silver Jubilee celebrations.

Opened to the public as a walkway in 1967, the abandoned nature of the Undercroft would initially attract the homeless. Some might say to encourage the public’s creativity, the Undercroft was left deliberately bare by its designers. A theory that would align well with the avant garde nature of the Archigram Collective, the neofuturistic architects involved with the development of what would become the South Bank Centre.

——————

Meanwhile in Venice Beach, California, surfers in the 1950s would experiment with box-carts during downtime, eventually developing skateboarding as we now recognise. Emulating surfing, they would ride the board as though a surfboard, hitting tricks against street furniture as though a solid wave.

The practice would evolve in a short time, and by the 1970s, several pro-skaters were beginning to make a name for themselves, and figures like Steve Caballero and Tony Hawk further popularised the activity. Crossing the Atlantic, a handful of people began practising this new pastime in UK parks and public spaces. Skateboarding would eventually hit the mainstream in the mid 70s, and continue into the 80s.

Skateboarding is a raw sport. A primal expression of physicality within a defined space and time. An art form born on the streets — pavements, step-streets and railings the materials to create and land tricks. The Undercroft’s topography allowed for such experimentation, to develop tricks and to ride with greater speed. To perfect the craft, skaters will repeat a trick relentlessly. It speaks of dedication and perseverance; the artistry of the sport, often outdoors, another boon.

Sites like the Undercroft grew in popularity. Minimal fixtures are present here, with a few scattered banks, ramps and mushroom columns holding the whole thing up upon smooth paving. Either side of a central base are two drops, ahead with more tantalisingly empty space. Naturally, skateboarding would come to dominate this architecturally unique site. Within ten years of opening to the public, the Undercroft was staging skateboarding events, including the UK Slalom Championships.

Southbank quickly became the London go-to skateboarding location. The Undercroft, the birthplace of British skateboarding. International recognition would follow, with skateboarders of from across the world travelling to the site to pay pilgrimage. And through it all the Undercroft has become the oldest, most continually skated spot in the world — a status not to be taken for granted.

Despite this, skateboarding is conflated with antisocial behaviour, depicted as transgressive at best, and worst, seen as the niche past time of the impoverished underclass that sits close to criminality. Graffiti, drug taking, underaged drinking, vandalism and all other ills of kids left alone unobserved. This parallel image has existed in various media too, with film popularising a narrative of stoner kids inflicting criminal damage to public spaces, congregating in threatening packs and howling at one another’s tricks.

Private security installed in 1983 would see the beginnings of tensions between the Southbank Centre and the Undercroft community. Barriers would render areas inaccessible; passed off as an electrical fault, evening lights were switched off as a deterrent. Active destruction would be employed. Holes drilled along banks and bollards. Each step altered the skatepark's original architecture. Temporary closures used as exhibition space were made permanent, anti-skateboarding fixtures were installed and existing structures ultimately destroyed.

Years of destruction would see the Undercroft footprint reduced to a fraction of its original design. Culminating with the permanent placement of a metal barrier in 2011 — finally demarcating the Queen’s Walk from the Undercroft skateboarders.

Perhaps best illustrating the fundamental disconnect between the Southbank Centre’s decision makers and the skateboarding community is that skateboarding continued to thrive within the Undercroft. The alterations proved only a temporary challenge. The art of skateboarding is to assess the terrain, respond with a board that is an extension of your body. The Undercroft skateboarders viewed these changes as just another physical obstacle that, embraced, would extend the language of their craft.

——————

The antisocial image of skateboarding grew. Hostilities towards the skateboarders within the Undercroft a microcosm reflecting mainstream society’s prejudices, and worryingly, increasingly towards marginalised groups.

Public spaces adorned with hostile architecture, targeting skateboarders, BMXers, graffiti artists and homeless people creates an othering. Benches have rivets, raised arm rests and bars, pyramidal tiles are scattered on pavements, strategically placed bolts on ledges, sloped windows all shift the problem caused by deeper structural issues within our society.

Excluding people who do not respond ‘appropriately’ to public spaces, dismissed as a movable entity. To the targeted group a constant reminder “to move on, go be weird over there.” Slim affecting a patrician tone discussing the Southbank Centre’s underestimation of the coordinating and campaigning power of the Undercroft members.

Our age of cynicism and intolerance feeds from this mindset. It fosters a culture where gutting an historical site and consequently disrupting a community is justified. Where the pursuit of financial reward takes precedence over the best use of public spaces.

On March 6th 2013, the Southbank Centre issued a press statement, stating:

“New undercroft venues - under-used space from the undercrofts will be reclaimed for artistic and cultural uses; including a new venue for gigs, dance, cabaret, music and spoken word events and a space for young people.”

Dubbed the Festival Wing Plan, the £110 million project would see the permanent closure of the Undercroft. A glass pavilion, new arts spaces, a literature centre, cafes and commercial units erected in its place. Artistic director Jude Kelly, calling the Undercroft “tired and undernourished”, engineered a £1m relocation plan with chief executive Alan Bishop and governing board chairman Rick Haythornthwaite. A custom built skatepark at Hungerford Bridge, no more than fifty yards along the Queen’s Walk, was proposed by the senior leadership to the skateboarding community.

“Everybody who looked at the plan just thought 'do you think I'm an idiot?’ They thought we were idiots. We took one look at the proposals and knew it was bad.

“What they offered us was just not adequate. It was under a bridge near London Bridge (sic), but you can't recreate this place.”

Slim, a compact, if not a slight Undercroft skateboarder — known for his balletic falls, rising back up with a bounce — echoes the Undercroft community’s thoughts. The proposal was unpalatable to the skateboarders. The injustice of destroying the sacred ground of the Undercroft, a wound which relocation to an anodyne site at Hungerford Bridge would doubtless salt.

“This place literally had the biggest political action among young people for over ten years. We fought hard for this place. You can tell who cares for this place. This is our home and if you treat it with respect, you'll get that respect back.”

The reappropriating of public spaces is rare and spontaneous. The growth of such places happens organically, slow, simmering to a new whole to be embraced by successive generations.

Folklore develops from never before seen tricks executed with aplomb. A custom built skatepark cannot replicate that history. Simply put, they don’t ride the same either. It's the difference between studio and street photography, chamber music and jazz. The Festival Wing Plan was doomed to fail from the outset; to destroy the Undercroft unfathomable.

The Inception of Long Live Southbank

Long Live Southbank began operating in April 2013 in direct response to the Southbank Centre’s Festival Wing Plan. The non-profit organisation quickly gained public support, registering 150,000 members within months of its inception. The swell of support would halt the Festival Wing Plan for six months.

Public support grew exponentially and on July 4th 2013, LLSB hand-delivered 14,000 individual planning objections to Lambeth Council, the largest number of signed objections to a planning application in British history.

The conceit of the Festival Wing Plans was flawed, the Undercroft proved culturally indispensable and the relocation plan was fully rejected by LLSB. Not only had they successfully campaigned to overturn the largest planning permission request in Europe, they succeeded in collaborating with the Southbank Centre’s senior leadership.

Six months into LLSB’s existence, on September 18th 2014, together with the Southbank Centre, signed a section 106 planning agreement with Lambeth Borough Council, guaranteeing the long term future of the Undercroft. A remarkable achievement, regardless of the plaintif’s stature.

By 2015, the Undercroft redevelopment proposal was submitted to the Southbank Centre. Lambeth Council approved the planning permission to restore the Undercroft to its former glory. The £790,000 outlay was successfully crowdfunded and restorations by Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios began at the Undercroft.

The plans of the Southbank Centre were overturned by the coming together of contemporaries united by shared ideals: to save the Undercroft, and go beyond by drawing back years of diminishing skate-space. It is born out of an understanding of the Undercroft, its history, a reverence towards a site we temporarily occupy. Custodians until the new pioneers arrive. The deeper meaning of the Undercroft was almost lost to the Southbank Centre. Its heritage, an active in situ cultural hotspot for which it is worth fighting.

ACCESS

I met Nate early into this journey. Always keen to share stories or explain technique, he stands above six foot, his rakish physique buoyant with lazy energy. Nate would be the first to criticise his current technique. Certainly his skating range retains enough fierceness to intimidate.

There is one other skateboarder, rolling and landing tricks alone. With the latest round of restrictions easing, we arranged to meet at the central base. Nate explains lightheartedly, messaging me forced his hand this morning. Lockdown inertia clearly still persisting.

Fumes of smoke occasionally flow through the Undercroft — serially smelling of barbecued chicken, or blazing herbs, that pique our collective interest, together trying to hint at the spring season that struggles to catch flight. The weather threatens a downpour at any second. Cold breezes blow through the empty hollow that catches our ill-dressed and static bodies.

What was the worst part of lockdown? His arms again gesticulate his animation at the question.

“That I have gotten worse since last year. I never thought that could happen. Other than breaking your legs (sic), I never felt like this could be taken away from me. My mind knows what to do but my body ain't getting the memo. It's like there's a disconnect.

“I feel slower to react and come off my board. I know I need to practice again to get to that level. There's a cognitive dissonance of knowing it takes the practice to relearn what feels like a stolen talent, but motivation is limited.”

——————

The talent on show is plenty, diverse and varied. Some flaunt more than others, others are more fluent. Some attract my eye more, draw my gaze. At the Undercroft the sight of skateboarders, BMX riders and scooters is often accompanied by graffiti artists, photographers and videographers. Occasionally models and musicians and dancers do their thing to the iconic backdrop. The graffiti and brutalist architecture provide a look no studio can replicate.

The Undercroft community bring their A-game and relentlessly practise to push further. Countless pretenders approach the barrier only to discreetly shuttle back into the throng of the Queen’s Walk.

Imagined it differently at the birthplace of British Skateboarding? It's raw. It's London. There's nothing like this place. We're among the National Theatre, the Houses of Parliament, iconic sites everywhere.

“There's a fear factor about this place. That everything is hyped up, like that ledge, it has an inverted slope. It's subtle, but you know when you get to it," explains Nate, meaning that it'll throw your momentum backwards if your approach lacks the know-how. Everything is faster, tricks are landed with force, the sounds more intense, grinding wheels and trucks that echo out through towards the River Thames. The spectacle of a midsummer Undercroft in full bloom is irresistible.

——————

Now the diaspora of tourists, skater fans and foes, photographers, children and adults all gaze and gawp at the wonders of the Undercroft, formulating their opinions on the Undercroft’s activity.

“Oh look, this is such a good idea to keep them off the streets,” whispers a passerby. The skateboarders’ compulsion to skate far outweighs any indignity of being viewed as a caged animal; skateboarding surely a quirk of youth.

At times eyes bulge, mobiles record video, hands and fingers point at an impressive sight ahead. Others, are stilled in utter bewilderment. Intrusive, self-interested, invasive are all uttered terms from skateboarders discussing photographers, with a healthy dose of suspicion towards the public looking into the Undercroft too.

About midway, there are subtle gaps at the base of the barrier. The rest is skirted with a series of wooden planks, placed there to protect runaway skateboards sliding into ankles and polished shoes on the Queen’s Walk. Yet the barrier serves to isolate the skateboarders to the Undercroft.

“We’re looked at like we’re in a zoo. I don’t like it myself.” Slim explains, as we discuss the barrier issue. Filipe interrupts our discussion on the attending crowd, his thoughts differing from Slim’s:

“See, we're all different, but I find it motivating. When you do tricks you're motivated, you’re skating for the crowd. It gets me confident to try to do it again and better. To see what I am doing and inspiring for the crowd.”

Filipe’s passion for the Undercroft and its community is clear to see, recounts that skateboarding is his saviour:

“Without skateboarding I could imagine not being in a good place. Who knows, in prison, selling drugs?”

Yet Slims insight into the importance of the Undercroft speaks for itself:

“It's an art form and it grows. People stand on others shoulders and see what they've done and emulate it. It becomes normal and other see that and it grows and grows.

“What I love about this place is seeing how skateboarding has developed. You look at old footage and people would ride the drop like it was a wave and now people bomb towards it and jump off.”

——————

The notion that this is their domain is inescapable. Their surface, an environment earned through slips and tricks and sweat dripped onto concrete — the sacred venue of British skateboarding.

Yes, you may observe, take photos if you must, but the Undercroft belongs to the skateboarders. We are rarely given access gratuitously. Access is granted through time, through credibility. Does the metal barrier burden the skateboarders through its unintended effect? Forced into a corner, a membership bound by a shared space and singular passion.

Why are these people so dedicated to this space? Why is it their calling? It is a passion to which I relate as a photographer. On multiple occasions I have found myself in awkward and challenging positions, shoots and shots that fail, yet I find myself returning to photography.

Do the skateboarders empathise with this; do they recognise what I’m saying? Am I wrong to think that the hours spent perfecting a move speaks the same language?

Gaining opportunities to shoot and interact with the Undercroft’ skateboarders would be no pushover. Credibility and honesty would be challenged and expected.

——————

“A girl just asked me for an interview and I told her straight up no. It’s hot to be natural, right?”

Filipe philosophising the perils of a skateboarder resting at the barrier.

——————

Early Saturday afternoon, I challenge myself to spend several hours at the barrier. Hoping to engage and not just take pretty pictures. I am starting to recognise the Undercroft regulars, their personalities taking shape.

“Can I sign into my Facebook?”

Leaning his back to the barrier, Noodle slowly turns to face me, as though to reassure me that this is completely normal, I have nothing to fear.

I hand over my phone, trying desperately to not think the worse. Logic follows that my dark thoughts are not justified. The converse is more risky, to be hasty and hedge caution would risk his distrust. We exchange words, explain what I’m about, he responds, eyes half cut, not necessarily from the afternoon sun. Dressed in whites and beige, dirt marks and holes patchwork his T-shirt and joggers, all hang loose upon a lean body.

“I spit and I’m an author. I have my own record label too.”

I don’t want to dismiss this as confabulation, a construct of this mental health that clearly oscillates between stable and, well, violence. Noodle continues, “I’ve had a psychotic episode...homeless now. Been in trouble with the feds, you know beating the shit out of some of them.” Again, is this an exaggeration to appease his ego while he finds himself lost?

We walk towards Hungerford Bridge. Noodle has a gliding nature to his movements, mixed with jitter, his hurried movements cause him to cover ground twice. There is a desperation in his eagerness to convey his talents and personhood. We’ve only just met but he has a loose, languid ease about his affect, relating to me without guard.

The bustling Christmas crowd aglow in the warm lights of the Christmas market, we stand out, a skater and a street photographer. He wants an audience, to attract people to his self-proclaimed talents. We stand beside a stall selling seasonal festive tat — trinkets that lose their charm when the mulled cider starts to wear off — nonetheless are lapped up.

Noodle’s spitting has not drawn a crowd; my barely audible phone held aloft, seemingly playing a silent beat. People walk past us, occasionally glancing, curious, unable to discern our aim. He has a thirst for another go, to spit to just one more track “and then I’ll let you go.” Perhaps he is self- aware enough to clock the absurd optics of us.

His lyrics detail the newly healed scars along his arms; tapping imagined keys multiple times to maintain his verbal rhythm. His homelessness doesn’t bode well with the oncoming winter, an autumn already biting. He is young though, his two piece tracksuit providing ample warmth, where I am shivering almost out of control.

My camera remains in my hand beside me. I’ve asked to shoot him a few times but I actually can’t raise my camera to do this, too scared to look into his eyes lest I reflect his coldness, a detached manner I am desperate to not judge him for.

I wish him well and tell him I’m back tomorrow.

——————

“This place is dirty. You don't want to see what the shower looks like after you've skated here. Brown water.”

A passing comment by a skateboarder who shall remain nameless. And yet they return, ready for another round of pounding concrete to chase that perfect land. Falling is as much part as landing a trick. It’s a messy past time. Scuffs and tears to garments that pick up grime from each fall.

A dedication to continue regardless of the times you hit the ground. A miss timed trick and the effect is immediate, palpable in its consequence. A natural motivator to improve, surely, a driver to control the unforgiving surface.

Building a catalogue of tricks is the ultimate aim, to attain enough competence to skate or pull tricks through involuntary thought. It requires years of practice, as much as any specialist activity. It speaks of motivation, counter to the current image of kids existing for the most part in the virtual. Here is a bold statement by young people of all backgrounds embracing the physical.

Feet that stroke the board and jab it nonchalantly into line while in quiet contemplation of the next move. Forward.

“See, that's the risk of doing this on your own!” Nate points affably to the lone guy hobbling over to the central base to recover, “you get cocky and do stuff that your body tells you you shouldn't do, but you do, because you always want to push yourself.

“It's a mad sport in some ways. You’re willingly go at this knowing you are gonna get hurt.”

Spatial awareness comes naturally to the skateboarder. Skateboarding demands it to execute tricks. A very three dimensional, visual memory orientated sport, requiring balance, quick reflexes, a chess player’s concentration; all speak of weapons an athlete brings to their sport.

Nate continues, “only sport where over thinking it isn't a bad thing.” Yet it's easy to be trapped in your head. Reality blurred by the limitations of seeing only what's in your own mind, stuck in an expanse limited by one's own criticism.

“It’s a thinking man's sport. You can live inside your head so easily at these times. And don't want to leave your house and just end up wasting time or money on wasteful things. Tell me to stop. Years from now I could be driving a Ferrari or something.”

Since the start of the pandemic, social isolation has invited rumination to too many, too often. I leave Nate to skate — after all this is a skatepark and he is a skateboarder.

——————

It's an aggressive sound, it's meant to intimidate. It crackles and scrapes against hard unforgiving concrete.

“There’s a barrier there.”

“I'm a skater too.”

“I don’t care, there’s a barrier over there. Just don’t stand there taking pictures.”

I clocked minutes earlier the agitated expressions, features contorting against the burning light of the peaked afternoon sun on Twiggy’s face. Twiggy skates fast. His push-offs seemingly accelerating further from his loose technique.

A civilian has entered. The man unlike them — with neat hair, a utilitarian bag over one shoulder, clothes worn and torn through falls and scrapes noticeably absent — has crouched beside a mushroom column to capture a dope shot. Twiggy comes to a grinding halt inches away, demanding fiercely his expulsion.

“Yes, he did that to me too, but we're friends now.” Slim recounts a similar low-tolerance threshold anecdote, relating to a snaking incident, where one skateboarder cuts the path of another skateboarder.

Startled at the public telling-off, the photographer departs. Perhaps embarrassed too for the misjudgment he showed nonchalantly entering the Undercroft.

——————

The swell of the Thames at its fullest this morning, the pull of the moon peaked, undulating waves brush the solid walls of the bank. It’s icy cold and grey. The graffitied walls seem desaturated. Pivots more aggressive, the sound of grinding wheels seem harsher today. Tricks not sticking yelled at more vehemently. Snaking more pronounced.

The Undercroft is relatively bare, a dissuasive rain keeping many home. Emboldened by the scarcity of skateboarders, despite my unease and tension, I walk in and sit along the central base. There are plenty of children too, mostly on the lower deck. Some are with their parents, and some have come as a group. Some are with pads and helmets. Others with just the right clothes.

I don’t feel welcomed today. The rising tension is evident. Our intrusion has doubtless affected the mood, caused a ripple. Focus taken away. The kid eyeballing me is one of these distracted souls, the most tense in the crowd. I ease away. I stand just under the balcony, sheltered from the rain, the wet surface around me avoided by the skateboarders.

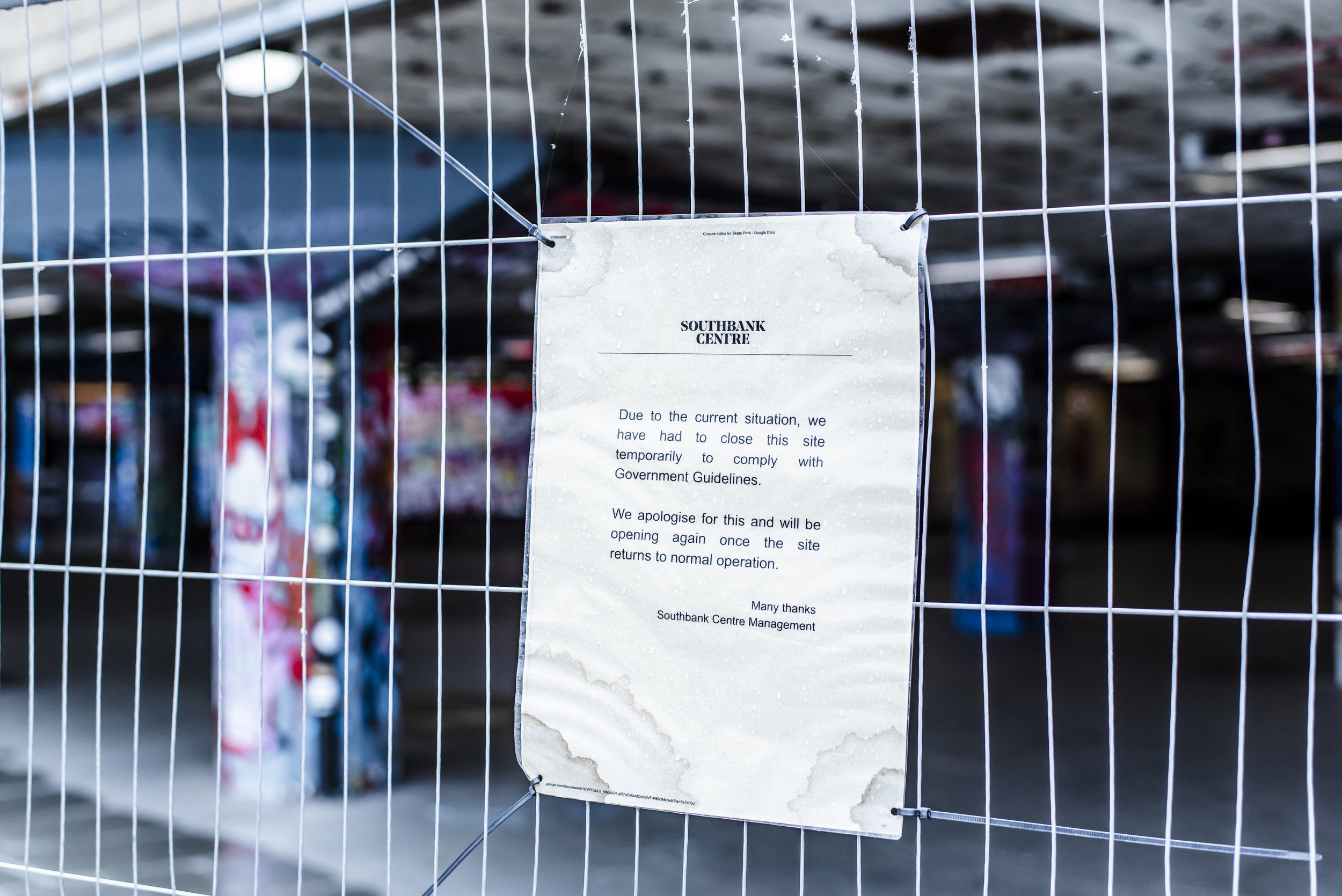

Tomorrow the UK enters another round of national lockdown. The third since the start of the pandemic, and having just entered the winter season, it is threatening to be the most challenging yet.

There has in recent weeks been a growing trend of people using the Undercroft as a hangout spot, with no intention of skateboarding. Reports of stealing; drugs and alcohol exchanged and consumed throughout, leaving the place a mess. Recordings of retaliation against these trespassers regularly do the rounds on social media. Beginning with water bottles thrown, escalating more recently to firecrackers lit and directed at the unassuming people.

“This is London after all, we’re a crime spot for the country,” an honesty from Nate from a past encounter, which indicates this is something to put up with, a natural part of life in the Undercroft.

My reverie snaps.

Another skater finds himself on the floor. You see, he landed the trick as par for the course, but felled by the snaked. Despite there being fewer skaters today, colliding with one another happens.

Hands shake or fists are bumped in mutual acknowledgment, yet today that understanding is blown away. Instead, a punch is landed squarely on his fellow skateboarder’s cheek. The skateboarder is floored. A rush of people head to stop this escalating further. The guy on the floor is up, and disconsolately walks to the concrete blocks, sitting not far from his attacker.

Pandemic & Beyond

The COVID-19 pandemic’s arrival irrevocably altered society. Our past daily activities — back then taken for granted — at times now look unrecognisable. Lockdowns throughout this crisis, testing humanity’s resolve to cope, imposing isolation throughout the globe. The everyday chatter a tool for grounding us socially; interactions with strangers, friends and family that enrich our existence irreplaceably lost.

The drama of the rights to public space that happened to the Undercroft is happening throughout the city. The pandemic has accelerated these shifts and perhaps broadened the prism through which the legitimacy of public spaces are viewed.

From the regeneration of town centres, to corporate owned public spaces — manoeuvring footfall through a parade of exclusive brands — cynically engineer social engagement around consumerism, threaten our social engagements.

What will our public spaces look like? Will society as a whole double down to support the status quo, or tap into the zeitgeist coming out of communities, daring to build an infrastructure to support endeavours beneficial to society.

What stops the commercialisation of the Undercroft? The space hired for corporate sponsorship?

In such pandemic times, public spaces like the Undercroft could be back on the negotiating table. The Undercroft community will be acutely aware of the challenge ahead and the new threats facing the Undercroft. The shape of society is there to be moulded, and if places missing the Undercroft’s cultural significance are to survive, the divide between the public and corporate interests must not widen.